GetX in Cubit Style for a Cooperative Finance App

How I brought a cubit like mental model, single state and explicit effects, into our GetX codebase to make UI predictable, composable, and testable.

Ahmad Fikril

November, 28th 2025

GetX in Cubit Style for a Cooperative Finance App

TL;DR

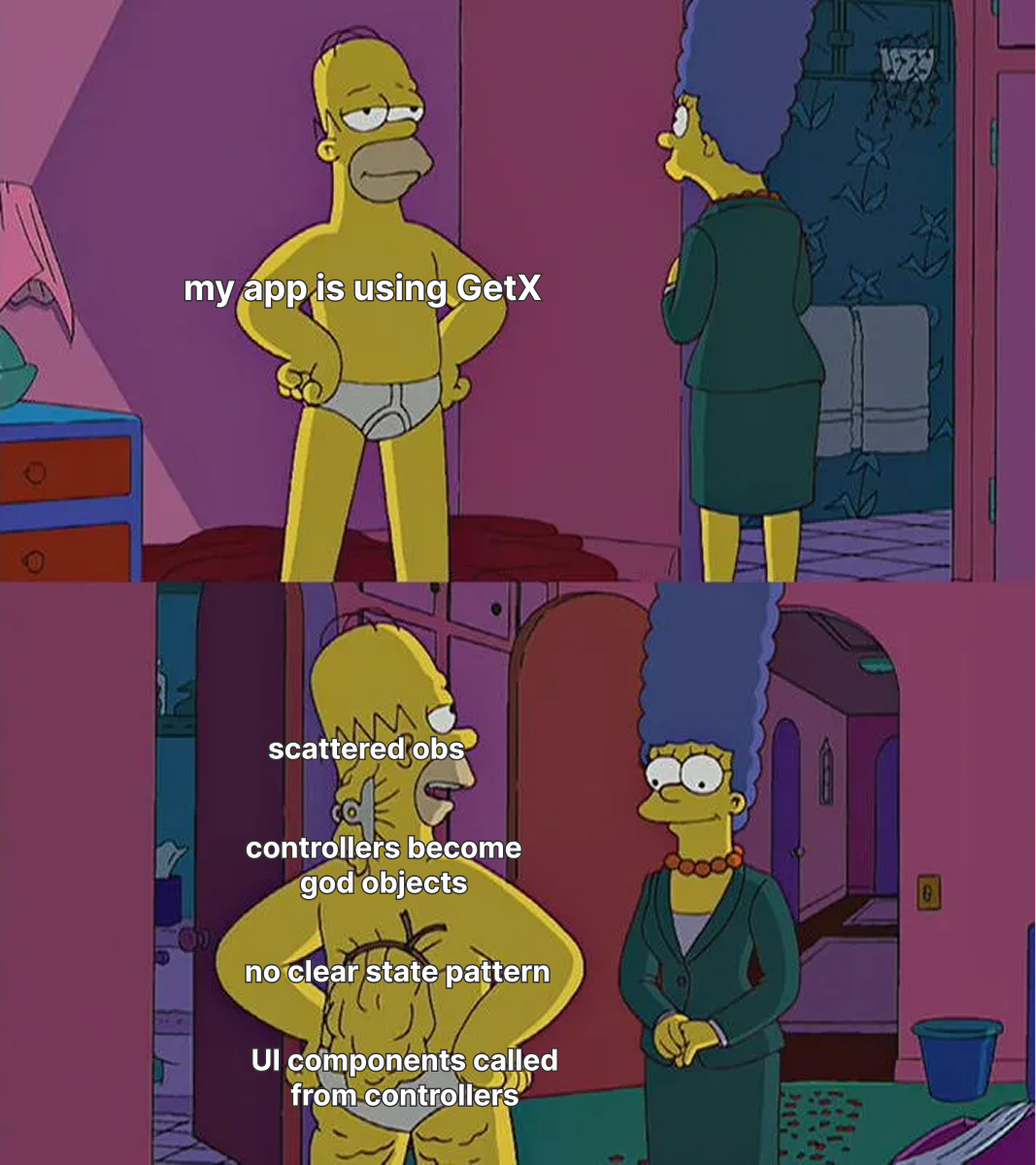

On an earlier project I abused GetX. I scattered many Rx fields per screen, triggered navigation

and snackbars directly from controllers, and let presentation logic leak everywhere. It worked, but

I kept hitting rebuild errors, subtle race conditions, and controllers that knew too much about the

UI.

In my Orymu side project I used Bloc and Cubit more deliberately and I liked how it forced me into a

single state per screen and explicit transitions. On the next cooperative finance app I decided to

keep GetX for routing and dependency injection, but reshape the presentation layer around that

Cubit mental model: one state stream per screen, a separate effect channel for one shots, and clear

rules for when to use sealed state or composite form state.

Context: where I started with GetX

KoperasiQu is a cooperative finance app for auth, balances, savings and loans, and transactions.

Before this project I had shipped a production app using GetX in a much less disciplined way.

Controllers were the place where everything went. I stored loading flags, errors, lists, filters,

pagination and even dialog state as separate Rx fields, and I also put navigation and snackbars

inside those controllers.

This trimmed version of a real controller from that period captures the pattern:

class AuthController extends GetxController {

final LoginUseCase _loginUseCase;

// ...

final isLoading = false.obs;

final isGoogleLoading = false.obs;

final errorMessage = RxnString();

final auth = Rxn<AuthEntity>();

final token = RxnString();

final userFullname = RxnString();

final userUid = RxnString();

final authRole = RxnString();

Future<void> login({

required String username,

required String password,

}) async {

isLoading.value = true;

errorMessage.value = null;

try {

final result = await _loginUseCase(

username: username,

method: 'password',

password: password,

);

auth.value = result;

token.value = result.authToken;

userFullname.value = result.userFullname;

userUid.value = result.userUid;

authRole.value = result.authRole;

Get.offAllNamed(HomeRoutes.main); // navigation from controller

} on AuthException catch (e) {

errorMessage.value = e.message;

} catch (err) {

errorMessage.value = err.toString();

} finally {

isLoading.value = false;

}

}

}Some other controllers were worse. A single approval controller held more than ten Rx fields for

loading, pagination, filters, errors, history, and processing flags. At the same time my views

Get.find those controllers directly, called methods on them, manually popped Navigator levels,

and decided whether to show snackbars based on controller flags. The responsibilities were blurred.

It was hard to answer a simple question like, what state is this screen in right now.

In practice this shape showed up as UI rebuild errors and subtle race conditions. Loaders could be stuck with old data, dialogs could close twice, and snackbars or navigation could trigger twice or not at all, depending on rebuild timing.

I can represent that messy flow conceptually like this:

Mermaid diagram loading…

GetX itself was not the problem. My lack of structure was.

Problem and constraints

Looking back at that code, a few concrete problems stand out.

- I had scattered observables. A typical screen kept

isLoading,items,errorMessage, pagination flags and filter values in differentRxfields. The UI could easily show old data with a new loading flag or lose inline errors when loading. - Controllers became god objects. They talked to use cases, held UI specific timers like

debounce, reached into other controllers withGet.find, and called navigation and snackbars directly. - There was no clear pattern for when to show loading, failure or success. Each screen invented its

own combination of flags and

Obxwidgets. - One shot actions were mixed into state. A retry could happen while the widget tree was rebuilding, which sometimes caused double navigation or duplicate snackbars.

- Dependency injection was hidden.

Get.findinside methods made it harder to see which collaborators a controller really depended on and made tests more awkward.

On this project I did not want to repeat this. At the same time I had real constraints.

- We decided to keep GetX for routing and dependency injection.

- I could not stop the project and rewrite everything in one go, so any new pattern had to be adoptable screen by screen.

I needed a presentation architecture that gave me a single source of truth per screen and a predictable way to handle one shot events, while still fitting into an existing GetX codebase.

Aha moment: Bloc and Cubit in Orymu

The pattern that finally clicked for me came from a side project, Orymu. On that app I built a library list screen with Bloc and Cubit. At first I was just impressed by how clean the UI looked when deciding between states.

BlocBuilder<LibraryListBloc, LibraryListState>(

builder: (context, state) {

return switch (state.status) {

LibraryListStatus.initial || LibraryListStatus.loading => _buildLoadingState(),

LibraryListStatus.failure => _buildErrorState(

state.errorMessage,

),

LibraryListStatus.success when state.items.isEmpty =>

const LibraryEmptyState(type: LibraryCardType.done),

LibraryListStatus.success => _buildList(state),

LibraryListStatus.loadingMore => _buildList(

state,

showFooterLoader: true,

),

};

},

)One builder, one status enum, and all UI branches for loading, empty, failure, list and load more

in a single switch. There were no scattered Rx flags and no question about where the loading

state should be handled.

When I opened the Bloc itself, the mental model became even clearer.

class LibraryListBloc extends Bloc<LibraryListEvent, LibraryListState> {

LibraryListBloc({required GetUserBooksUseCase getUserBooks})

: _getUserBooks = getUserBooks,

super(const LibraryListState()) {

on<LibraryListStarted>(_onStarted);

on<LibraryListNextPageRequested>(_onNextPageRequested);

on<LibraryListFilterChanged>(_onFilterChanged);

on<LibraryListRefreshed>(_onRefreshed);

on<LibraryListIncludePrivateChanged>(_onIncludePrivateChanged);

on<LibraryListGenreChanged>(_onGenreChanged);

on<LibraryListSearchChanged>(_onSearchChanged);

on<LibraryListDetailResultApplied>(_onDetailResultApplied);

}

final GetUserBooksUseCase _getUserBooks;

Future<void> _onNextPageRequested(

LibraryListNextPageRequested event,

Emitter<LibraryListState> emit,

) async {

if (!state.hasNextPage || state.isLoadingMore) return;

final nextPage = state.page + 1;

emit(state.copyWith(status: LibraryListStatus.loadingMore, page: nextPage));

await _fetchPage(emit, page: nextPage, resetList: false);

}

Future<void> _fetchPage(

Emitter<LibraryListState> emit, {

required int page,

required bool resetList,

}) async {

final result = await _getUserBooks(

page: page,

limit: state.limit,

status: state.statusFilter,

includePrivate: state.includePrivate,

genre: state.genre,

search: state.search,

sort: state.sort,

);

result.fold(

(failure) => emit(

state.copyWith(

status: LibraryListStatus.failure,

errorMessage: failure.userMessage,

page: resetList ? 1 : (state.page > 1 ? state.page - 1 : 1),

),

),

(paginated) {

final updatedItems =

resetList ? paginated.items : [...state.items, ...paginated.items];

emit(

state.copyWith(

status: LibraryListStatus.success,

items: updatedItems,

hasNextPage: paginated.hasNext,

errorMessage: null,

),

);

},

);

}

}Every user intent was an event, the Bloc held one LibraryListState that contained items, filters

and pagination, and there was a single _fetchPage that mapped use case results into a new state.

Even one shot effects, such as a toast after a book was removed, were modelled as an effect field

that I set and cleared explicitly.

Compared to my old GetX screens with many Rx flags and controller driven navigation, this felt

like there was finally one place where the truth lived. I liked how Cubit and Bloc forced me into

single state and explicit transitions and I wanted to bring that mental model back into a GetX

codebase.

I can summarise that cleaner flow like this.

Mermaid diagram loading…

Decision: bringing a Cubit mental model into GetX

I decided to keep GetX for routing and dependency injection, but to treat each GetX controller more like a Cubit. At first my rules were simple: one sealed state per screen for fetch flows, plus an optional effect channel for one shot navigation and snackbars. I applied that same sealed pattern everywhere, including forms, and only later realised that complex forms were a different beast.

Over time those rules evolved into something more concrete.

- Each screen should have one reactive state. For fetch and display screens this is usually a sealed

state with variants like

Initial,Loading,Empty,Data,Failure. For form heavy screens this later became a composite state that holds a form snapshot, a status enum and request error information. - One optional effect channel per screen. Controllers expose

Rxn<Effect>for navigation, dialogs and snackbars so that one shot actions do not leak into state and do not depend on rebuild timing. - Controller methods represent user intents. They orchestrate use cases and map results into a new

state or an effect. They do not call

Get.offAllNamedorGet.snackbardirectly. - Constructor injection instead of hidden

Get.find. Bindings are responsible for wiring collaborators so tests can construct controllers with fake dependencies.

I also wanted this to be a team pattern, not a personal habit. That is why I pulled the rules and examples into our UI state architecture guide, including a decision matrix for when to use sealed versus composite state, and a list of anti patterns to avoid.

At a high level the new flow for a screen looks like this.

Mermaid diagram loading…

Solution overview

From these decisions the concrete shape of the presentation layer I use now looks like this. I first applied it on this cooperative finance app and then carried the same pattern into newer projects:

- One reactive state per screen.

- Sealed state for fetch and display flows, including pagination.

- Composite state for form heavy flows like sign in, sign up, PIN and KYC.

- An optional effect channel per screen, backed by

Rxn<Effect>, for navigation, dialogs and snackbars. - Views that use a single

Obxto render state and a singleeverlistener to react to effects. - Controllers that use constructor injection for use cases and helper services and map their results into state and effects.

In the rest of this case study I will walk through two concrete examples that shaped the pattern, and then show how I used effects to clean up navigation and snackbar races.

Example: composite form for sign up

Sign up was my first test of a composite form pattern inside this new GetX style. I wanted a state that could hold a full snapshot of the form, a status for the current request and any error coming back from the server, so that inline validation and request failures would not fight each other.

This is the simplified shape of the state.

enum SignUpRequestStatus { idle, submitting, success, failure }

class SignUpFormView {

final String? fullnameError;

final String? phoneError;

final String? passwordError;

final String? confirmPasswordError;

final String? formMessage;

final String? coopError;

final bool requireConfirmPassword;

const SignUpFormView({

this.fullnameError,

this.phoneError,

this.passwordError,

this.confirmPasswordError,

this.formMessage,

this.coopError,

this.requireConfirmPassword = true,

});

SignUpFormView copyWith({

String? fullnameError,

String? phoneError,

String? passwordError,

String? confirmPasswordError,

String? formMessage,

String? coopError,

bool? requireConfirmPassword,

}) {

return SignUpFormView(

fullnameError: fullnameError ?? this.fullnameError,

phoneError: phoneError ?? this.phoneError,

passwordError: passwordError ?? this.passwordError,

confirmPasswordError: confirmPasswordError ?? this.confirmPasswordError,

formMessage: formMessage ?? this.formMessage,

coopError: coopError ?? this.coopError,

requireConfirmPassword:

requireConfirmPassword ?? this.requireConfirmPassword,

);

}

}

class SignUpState {

final SignUpFormView form;

final SignUpRequestStatus status;

final String? requestError;

final SignInDataEntity? data;

const SignUpState({

this.form = const SignUpFormView(),

this.status = SignUpRequestStatus.idle,

this.requestError,

this.data,

});

SignUpState copyWith({

SignUpFormView? form,

SignUpRequestStatus? status,

String? requestError,

SignInDataEntity? data,

}) {

return SignUpState(

form: form ?? this.form,

status: status ?? this.status,

requestError: requestError ?? this.requestError,

data: data ?? this.data,

);

}

}Before I reached this composite shape I tried to stick with the sealed pattern everywhere. My first

version of the sign up state was a sealed SignUpState with a SignUpForm variant that held all

field errors and formMessage, plus SignUpLoading, SignUpSuccess and SignUpFailure. It looked

neat in code, but it did not match how the screen actually behaves.

- In the real UI the form is always visible, even while loading or after a failure. In the sealed

type the form only existed in the

SignUpFormvariant, so when the state moved toSignUpLoadingorSignUpFailureI had to fall back to aconst SignUpForm()just to keep the widget tree happy. The type was effectively saying that the form disappeared, but the UI never removed it. - Banner messages were split across variants. Inline validation lived in

formMessageonSignUpForm, while server errors lived inSignUpFailure.message. Both the controller and the view had to remember where to put and where to read the message from, which became noisy once I started adding more cases. - Some natural combinations were awkward or impossible to express without inventing more variants.

For example, keeping the previous validation banner visible while a request is loading, or showing

field level errors and a server error banner at the same time, would have pushed me towards extra

variants like

SignUpLoadingWithFormorSignUpFailureWithForm. I could feel the state space starting to explode.

As a temporary band aid I added helpers like viewForm, isLoading and uiMessage so the page did

not have to pattern match on all the sealed variants, and I faked a default form when the state was

not SignUpForm. That worked, but it was a sign that the sealed model did not really match the way

I thought about the screen.

The controller exposes just one Rx<SignUpState> plus an optional effect stream for navigation. On

every field change it validates that field, updates the form snapshot via a copy, and clears any

previous requestError. On submit it sets status to submitting, calls the use case, then sets

status, requestError and data based on the result, and emits a NavigateToHomeEffect when it

is time to move on.

The view reads everything it needs from a single reactive state, through small helpers.

Obx(() {

final s = controller.state.value;

final form = s.form;

final isLoading = s.status == SignUpRequestStatus.submitting;

final uiMessage = s.requestError ?? form.formMessage;

// build fields with inline errors from form

// show loading button state from isLoading

// show error banner from uiMessage

// ...

})This composite form pattern fixed some of the pain I had in the past. The form snapshot is always present, there is no casting from sealed variants in the view, and inline errors stay visible during loading and failure instead of being lost whenever the state changes.

Conceptually the sign up flow looks like a simple state machine.

Mermaid diagram loading…

The important part is that form lives inside all of these states, so the UI never has to

reconstruct it from scratch.

Example: sealed fetch and pagination for EVA mutation

On previous projects my list and pagination screens looked a lot like the approval controller I

showed earlier. I had flags like _isLoading, _hasMore, _isError, _isUnauthorized,

_isLoadingHistory and _historyHasMore living next to the lists, and the view tried to interpret

combinations of those flags to decide whether to show a loader, an empty state, or an error.

In this app I decided to treat EVA mutation as my testbed for a sealed pagination pattern that follows the same idea as the Orymu library list but in GetX.

The state is sealed, and the data variant keeps both items and pagination flags together.

sealed class EvaMutationState {

const EvaMutationState();

}

class EvaMutationInitial extends EvaMutationState {

const EvaMutationInitial();

}

class EvaMutationLoading extends EvaMutationState {

const EvaMutationLoading();

}

class EvaMutationEmpty extends EvaMutationState {

const EvaMutationEmpty();

}

class EvaMutationFailure extends EvaMutationState {

final String message;

const EvaMutationFailure(this.message);

}

class EvaMutationData extends EvaMutationState {

final List<EvaMutationEntity> items;

final int page;

final bool canLoadMore;

final bool isRefreshing;

final bool isLoadingMore;

const EvaMutationData({

required this.items,

required this.page,

required this.canLoadMore,

this.isRefreshing = false,

this.isLoadingMore = false,

});

EvaMutationData copyWith({

List<EvaMutationEntity>? items,

int? page,

bool? canLoadMore,

bool? isRefreshing,

bool? isLoadingMore,

}) {

return EvaMutationData(

items: items ?? this.items,

page: page ?? this.page,

canLoadMore: canLoadMore ?? this.canLoadMore,

isRefreshing: isRefreshing ?? this.isRefreshing,

isLoadingMore: isLoadingMore ?? this.isLoadingMore,

);

}

}The GetX controller holds a single Rx<EvaMutationState> and guards load, refresh and load more to

avoid double fetches.

class EvaMutationController extends GetxController {

final GetEvaMutationsUseCase _getEvaMutations;

EvaMutationController(this._getEvaMutations);

final Rx<EvaMutationState> state = const EvaMutationInitial().obs;

Future<void> loadFirstPage() async {

state.value = const EvaMutationLoading();

final res = await _getEvaMutations(page: 0, size: 10);

res.fold(

(f) => state.value = EvaMutationFailure(f.toUiMessage()),

(page) {

final items = page.items;

if (items.isEmpty) {

state.value = const EvaMutationEmpty();

} else {

state.value = EvaMutationData(

items: items,

page: page.currentPage,

canLoadMore: page.hasNext,

);

}

},

);

}

Future<void> loadMore() async {

final s = state.value;

if (s is! EvaMutationData || !s.canLoadMore || s.isLoadingMore) return;

state.value = s.copyWith(isLoadingMore: true);

final nextPage = s.page + 1;

final res = await _getEvaMutations(page: nextPage, size: 10);

res.fold(

(f) => state.value = s.copyWith(isLoadingMore: false),

(page) {

final newItems = [

...s.items,

...page.items,

];

state.value = EvaMutationData(

items: newItems,

page: page.currentPage,

canLoadMore: page.hasNext,

);

},

);

}

}The view mirrors the Orymu BlocBuilder idea with a single Obx that switches on state.

Obx(() {

final s = controller.state.value;

switch (s) {

case EvaMutationInitial():

return const SizedBox.shrink();

case EvaMutationLoading():

return _buildLoading();

case EvaMutationEmpty():

return _buildEmpty();

case EvaMutationFailure(:final message):

return _buildError(message);

case EvaMutationData(:final items, :final isLoadingMore):

return _buildList(items, showFooterLoader: isLoadingMore);

}

})Now one snapshot holds both the items and all of the pagination flags. There is no need to

coordinate separate RxList and RxBool fields, and the transitions are predictable, such as

Loading to Empty or Data, and Data with isLoadingMore set to show a footer spinner.

Effects: fixing navigation and snackbar races

In my earlier GetX code controllers called Get.offAllNamed and Get.snackbar directly. Combined

with many Obx widgets and dialogs that built their own reactive trees, this easily caused double

navigation or duplicate snackbars when a method was triggered from multiple places or when the

widget tree rebuilt in the middle of an action.

In this codebase I separated these one shot actions into a dedicated effect channel. Controllers

expose Rxn<Effect>, and pages subscribe once in initState using ever. The controller sets an

effect when something should happen exactly once and then clears it. The view owns the actual

navigation and snackbar calls.

The pattern looks like this.

sealed class AuthEffect {

const AuthEffect();

}

class NavigateHomeEffect extends AuthEffect {

const NavigateHomeEffect();

}

class ShowErrorSnackbarEffect extends AuthEffect {

final String message;

const ShowErrorSnackbarEffect(this.message);

}

class SignInController extends GetxController {

final SignInUseCase _signIn;

SignInController(this._signIn);

final Rx<AuthState> state = const AuthInitial().obs;

final Rxn<AuthEffect> effect = Rxn<AuthEffect>();

Future<void> submit(String username, String password) async {

state.value = const AuthLoading();

final res = await _signIn(username: username, password: password);

res.fold(

(f) {

state.value = AuthFailure(f.toUiMessage());

effect.value = ShowErrorSnackbarEffect(f.toUiMessage());

},

(data) {

state.value = AuthSuccess(data);

effect.value = const NavigateHomeEffect();

},

);

}

}In the page I listen to effects once and handle them in the UI layer.

late final SignInController controller;

Worker? _effectWorker;

@override

void initState() {

super.initState();

controller = Get.find<SignInController>();

_effectWorker = ever<AuthEffect?>(

controller.effect,

(e) {

if (e == null) return;

switch (e) {

case NavigateHomeEffect():

Get.offAllNamed(HomeRoutes.main);

case ShowErrorSnackbarEffect(:final message):

_showErrorSnackbar(message);

}

controller.effect.value = null; // consume once

},

);

}

@override

void dispose() {

_effectWorker?.dispose();

super.dispose();

}This small change removed an entire class of bugs. Controllers no longer know about Navigator or

presentation details and one shot actions no longer depend on rebuild timing. The view remains the

single place that decides how to present navigation and messages.

Impact

Adopting this Cubit style presentation architecture inside GetX changed how I think about screens.

- The UI became more predictable. Single state per screen eliminated races between separate

Rxfields and made it easier to reason about what the user should see after each action. - Views became simpler. Each page has one

Obxthat switches on state and a single effect listener, instead of many smallObxwidgets bound to different flags. - Navigation and snackbars became safer. Effects removed double or missing one shot actions that were previously caused by controller driven calls and rebuild races.

- Testing improved. Controllers now depend on injected use cases and services and expose one state stream, which is straightforward to assert on in unit tests.

- New features have a clear default. The decision matrix for sealed versus composite state and the examples for sign up and EVA mutation give the team a shared pattern to follow.

What I learned

Working through this refactor taught me that GetX is not inherently messy or clean. The difference comes from the discipline I apply around state and effects. Bringing a Cubit mental model into a GetX codebase gave me a simple rule, one state and one optional effect per screen, and that rule reduced a lot of accidental complexity.

I also learned that writing down the rules matters as much as the code. The technical guides and case studies in this repo, including the UI state architecture and this story, help me and future teammates avoid repeating the same anti patterns and instead reach for a small set of well understood patterns when building new screens.

I did not start this work with a perfect three point rule in mind. I began with sealed state plus effects everywhere, then discovered through the sign up and other form flows that complex forms wanted a composite form, status and messages state instead. Only after that did the pattern crystallise in my head as three pillars: sealed state for fetch and pagination, composite state for form heavy screens, and a separate effect channel for one shot navigation and snackbars.